Chapter 8 Dense neural networks

Like we discussed in the previous overview, these three chapters on deep learning for text are organized by network architecture, rather than by outcome type as we did in Chapters 6 and 7. We’ll use Keras with its Tensorflow backend for these deep learning models; Keras is a well-established framework for deep learning with bindings in Python and, via reticulate (Ushey, Allaire, and Tang 2021), R. Keras provides an extensive, high-level API for creating and training many kinds of neural networks, but less support for resampling and preprocessing. Throughout this and the next chapters, we will demonstrate how to use tidymodels packages together with Keras to address these tasks.

The tidymodels framework of R packages is modular, so we can use it for certain parts of our modeling analysis without committing to it entirely, when appropriate.

This chapter explores one of the most straightforward configurations for a deep learning model, a densely connected neural network. This is typically not a model that will achieve the highest performance on text data, but it is a good place to start to understand the process of building and evaluating deep learning models for text. We can also use this type of network architecture as a bridge between the bag-of-words approaches we explored in detail in Chapters 6 and 7 to the approaches beyond bag-of-words we will use in Chapters 9 and 10. Deep learning allows us to incorporate not just word counts but also word sequences and positions.

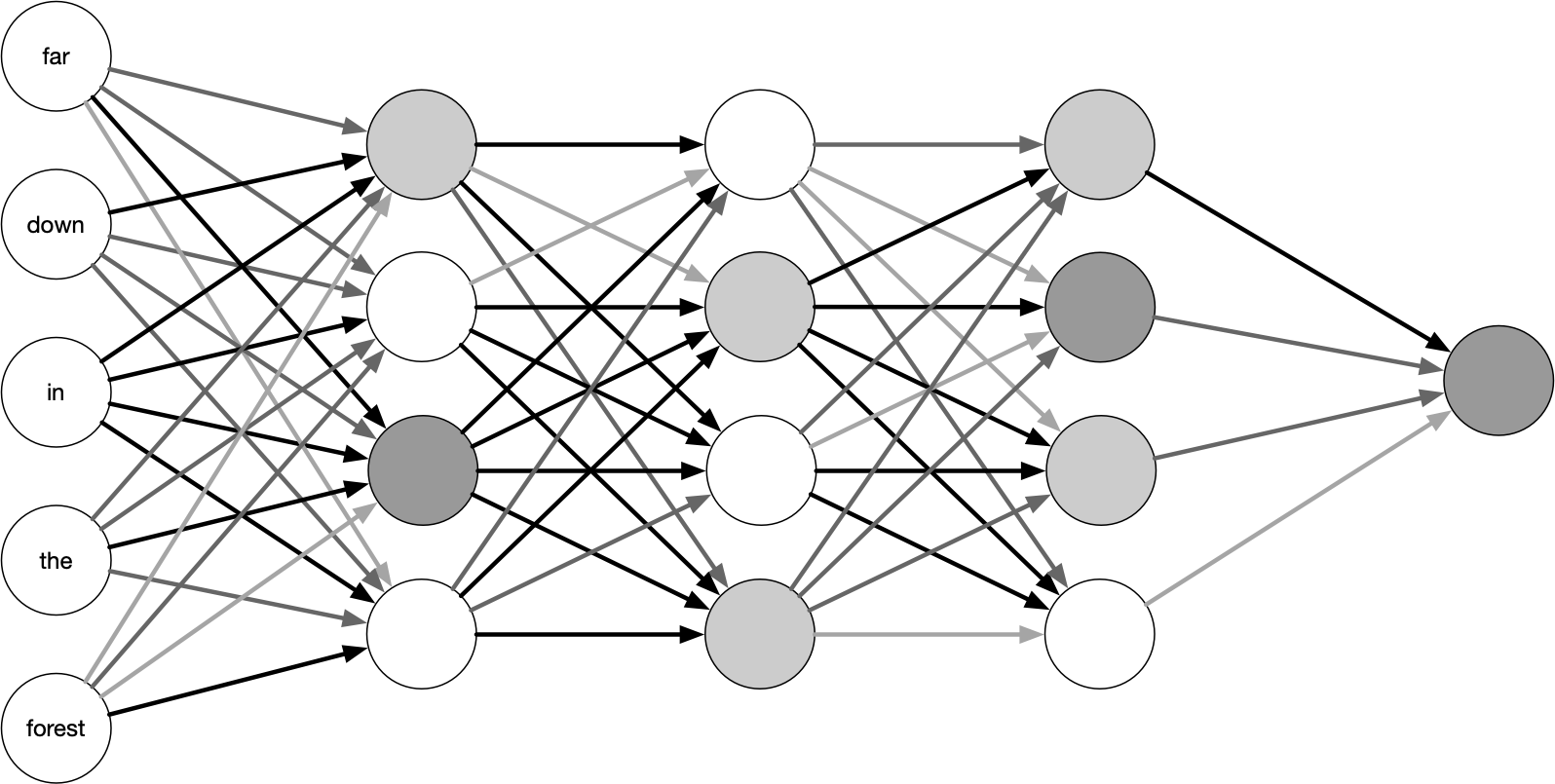

Figure 8.1 depicts a densely-connected neural network architecture feed-forward. The input comes in to the network all at once and is densely (in this case, fully) connected to the first hidden layer. A layer is “hidden” in the sense that it doesn’t connect to the outside world; the input and output layers take care of this. The neurons in any given layer are only connected to the next layer. The numbers of layers and nodes within each layer are variable and are hyperparameters of the model selected by the practitioner.

FIGURE 8.1: A high-level diagram of a feed-forward neural network. The lines connecting the nodes are shaded differently to illustrate the different weights connecting units.

Figure 8.1 shows the input units with words, but this is not an entirely accurate representation of a neural network. These words will in practice be represented by embedding vectors because these networks can only work with numeric variables.

8.1 Kickstarter data

For all our chapters on deep learning, we will build binary classification models, much like we did in Chapter 7, but we will use neural networks instead of shallow learning models. As we discussed in the overview to these deep learning chapters, much of the overall model process will look the same, but we will use a different kind of algorithm. We will use a data set of descriptions or “blurbs” for campaigns from the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter.

library(tidyverse)

kickstarter <- read_csv("data/kickstarter.csv.gz")

kickstarter#> # A tibble: 269,790 × 3

#> blurb state created_at

#> <chr> <dbl> <date>

#> 1 Exploring paint and its place in a digital world. 0 2015-03-17

#> 2 Mike Fassio wants a side-by-side photo of me and Hazel eati… 0 2014-07-11

#> 3 I need your help to get a nice graphics tablet and Photosho… 0 2014-07-30

#> 4 I want to create a Nature Photograph Series of photos of wi… 0 2015-05-08

#> 5 I want to bring colour to the world in my own artistic skil… 0 2015-02-01

#> 6 We start from some lovely pictures made by us and we decide… 0 2015-11-18

#> 7 Help me raise money to get a drawing tablet 0 2015-04-03

#> 8 I would like to share my art with the world and to do that … 0 2014-10-15

#> 9 Post Card don’t set out to simply decorate stories. Our goa… 0 2015-06-25

#> 10 My name is Siu Lon Liu and I am an illustrator seeking fund… 0 2014-07-19

#> # … with 269,780 more rowsThe state of each observation records whether the campaign was successful in its crowdfunding goal; a value of 1 means it was successful and a value of 0 means it was not successful. The texts for the campaign descriptions, contained in blurb, are short, less than a few hundred characters. What is the distribution of characters?

kickstarter %>%

ggplot(aes(nchar(blurb))) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1, alpha = 0.8) +

labs(x = "Number of characters per campaign blurb",

y = "Number of campaign blurbs")FIGURE 8.2: Distribution of character count for Kickstarter campaign blurbs

Figure 8.2 shows that the distribution of characters per blurb is right-skewed, with two thresholds. Individuals creating campaigns don’t have much space to make an impression, so most people choose to use most of it! There is an oddity in this chart, a steep drop somewhere between 130 and 140 with another threshold around 150 characters. Let’s investigate to see if we can find the reason.

We can use count() to find the most common blurb length.

kickstarter %>%

count(nchar(blurb), sort = TRUE)#> # A tibble: 151 × 2

#> `nchar(blurb)` n

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 135 26827

#> 2 134 18726

#> 3 133 14913

#> 4 132 13559

#> 5 131 11320

#> 6 130 10085

#> 7 129 8786

#> 8 128 7874

#> 9 127 7239

#> 10 126 6590

#> # … with 141 more rowsLet’s use our own eyes to see what happens around this cutoff point. We can use slice_sample() to draw a few random blurbs.

Were the blurbs truncated at 135 characters? Let’s look at some blurbs with exactly 135 characters.

set.seed(1)

kickstarter %>%

filter(nchar(blurb) == 135) %>%

slice_sample(n = 5) %>%

pull(blurb)#> [1] "A science fiction/drama about a young man and woman encountering beings

not of this earth. Armed with only their minds to confront this"

#> [2] "No, not my virginity. That was taken by a girl named Ramona the night

of my senior prom. I'm talking about my novel, THE USE OF REGRET."

#> [3] "In a city where the sun has stopped rising, the music never stops. Now

only a man and his guitar can free the people from the Red King."

#> [4] "First Interfaith & Community FM Radio Station needs transmitter in

Menifee, CA Programs online, too CLICK PHOTO ABOVE FOR OUR CAT VIDEO"

#> [5] "This documentary asks if the twenty-four hour news cycle has altered

people's opinions of one another. We explore unity in one another."All of these blurbs appear coherent and some of them even end with a period to end the sentence. Let’s now look at blurbs with more than 135 characters to see if they are different.

set.seed(1)

kickstarter %>%

filter(nchar(blurb) > 135) %>%

slice_sample(n = 5) %>%

pull(blurb)#> [1] "This is a puzzle game for the Atari 2600. The unique thing about this

is that (some) of the cartridge cases will be made out of real wood, hand

carved"

#> [2] "Art supplies for 10 girls on the east side of Detroit to make drawings

of their neighborhood, which is also home to LOVELAND's Plymouth microhood"

#> [3] "Help us make a video for 'Never', one of the most popular songs on

Songs To Wear Pants To and the lead single from Your Heart's upcoming album

Autumn."

#> [4] "Pyramid Cocoon is an interactive sculpture to be installed during the

Burning Man Festival 2010. Users can rest, commune or cocoon in the piece"

#> [5] "Back us to own, wear, or see a show of great student art we've

collected from Artloop partner schools in NYC. The $ goes right back to art

programs!"All of these blurbs also look fine so the strange distribution doesn’t seem like a data collection issue.

The kickstarter data set also includes a created_at variable; let’s explore that next. Figure 8.3 is a heatmap of the lengths of blurbs and the time the campaign was posted.

kickstarter %>%

ggplot(aes(created_at, nchar(blurb))) +

geom_bin2d() +

labs(x = NULL,

y = "Number of characters per campaign blurb")FIGURE 8.3: Distribution of character count for Kickstarter campaign blurbs over time

That looks like the explanation! It appears that at the end of 2010 there was a policy change in the blurb length, shortening from 150 characters to 135 characters.

kickstarter %>%

filter(nchar(blurb) > 135) %>%

summarise(max(created_at))#> # A tibble: 1 × 1

#> `max(created_at)`

#> <date>

#> 1 2010-10-20We can’t say for sure if the change happened on 2010-10-20, but that is the last day a campaign was launched with more than 135 characters.

8.2 A first deep learning model

Like all our previous modeling, our first step is to split our data into training and testing sets. We will still use our training set to build models and save the testing set for a final estimate of how our model will perform on new data.

It is very easy to overfit deep learning models, so an unbiased estimate of future performance from a test set is more important than ever.

We use initial_split() to define the training and testing splits. We will focus on modeling the blurb alone in these deep learning chapters. Also, we will restrict our modeling analysis to only include blurbs with more than 15 characters, because the shortest blurbs tend to consist of uninformative single words.

library(tidymodels)

set.seed(1234)

kickstarter_split <- kickstarter %>%

filter(nchar(blurb) >= 15) %>%

initial_split()

kickstarter_train <- training(kickstarter_split)

kickstarter_test <- testing(kickstarter_split)There are 202,092 blurbs in the training set and 67,365 in the testing set.

8.2.1 Preprocessing for deep learning

Preprocessing for deep learning models is different from preprocessing for most other text models. These neural networks model sequences, so we have to choose the length of sequences we would like to include. Documents that are longer than this length are truncated (information is thrown away), and documents that are shorter than this length are padded with zeroes (an empty, non-informative value) to get to the chosen sequence length. This sequence length is a hyperparameter of the model, and we need to select this value such that we don’t:

overshoot and introduce a lot of padded zeroes, which would make the model hard to train, or

undershoot and cut off too much informative text from our documents.

We can use the count_words() function from the tokenizers package to calculate the number of words and generate a histogram in Figure 8.4. Notice how we are only using the training data set to avoid data leakage when selecting this value.

kickstarter_train %>%

mutate(n_words = tokenizers::count_words(blurb)) %>%

ggplot(aes(n_words)) +

geom_bar() +

labs(x = "Number of words per campaign blurb",

y = "Number of campaign blurbs")FIGURE 8.4: Distribution of word count for Kickstarter campaign blurbs

Given that we don’t have many words for this particular data set to begin with, let’s err on the side of longer sequences so we don’t lose valuable data. Let’s try 30 words for our threshold max_length, and let’s include 20,000 words in our vocabulary.

library(textrecipes)

max_words <- 2e4

max_length <- 30

kick_rec <- recipe(~ blurb, data = kickstarter_train) %>%

step_tokenize(blurb) %>%

step_tokenfilter(blurb, max_tokens = max_words) %>%

step_sequence_onehot(blurb, sequence_length = max_length)

kick_rec#> Recipe

#>

#> Inputs:

#>

#> role #variables

#> predictor 1

#>

#> Operations:

#>

#> Tokenization for blurb

#> Text filtering for blurb

#> Sequence 1 hot encoding for blurbThe formula used to specify this recipe ~ blurb does not have an outcome, because we are using recipes and textrecipes functions on their own, outside of the rest of the tidymodels framework; we don’t need to know about the outcome here.

This preprocessing recipe tokenizes our text (Chapter 2) and filters to keep only the top 20,000 words, but then it transforms the tokenized text in a new way to prepare for deep learning that we have not used in this book before, using step_sequence_onehot().

8.2.2 One-hot sequence embedding of text

The function step_sequence_onehot() transforms tokens into a numeric format appropriate for modeling, like step_tf() and step_tfidf(). However, it is different in that it takes into account the order of the tokens, unlike step_tf() and step_tfidf(), which do not take order into account.

Steps like step_tf() and step_tfidf() are used for approaches called “bag of words,” meaning the words are treated like they are just thrown in a bag without attention paid to their order.

Let’s take a closer look at how step_sequence_onehot() works and how its parameters will change the output.

When we use step_sequence_onehot(), two things happen. First, each word is assigned an integer index. You can think of this as a key-value pair of the vocabulary. Next, the sequence of tokens is replaced with the corresponding indices; this sequence of integers makes up the final numeric representation. Let’s illustrate with a small example:

small_data <- tibble(

text = c("Adventure Dice Game",

"Spooky Dice Game",

"Illustrated Book of Monsters",

"Monsters, Ghosts, Goblins, Me, Myself and I")

)

small_spec <- recipe(~ text, data = small_data) %>%

step_tokenize(text) %>%

step_sequence_onehot(text, sequence_length = 6, prefix = "")

prep(small_spec)#> Recipe

#>

#> Inputs:

#>

#> role #variables

#> predictor 1

#>

#> Training data contained 4 data points and no missing data.

#>

#> Operations:

#>

#> Tokenization for text [trained]

#> Sequence 1 hot encoding for text [trained]

What does the function prep() do? Before when we have used recipes, we put them in a workflow() that handles low-level processing. The prep() function will compute or estimate statistics from the training set; the output of prep() is a prepped recipe.

Once we have the prepped recipe, we can tidy() it to extract the vocabulary, represented in the vocabulary and token columns10.

prep(small_spec) %>%

tidy(2)#> # A tibble: 14 × 4

#> terms vocabulary token id

#> <chr> <int> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 text 1 adventure sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 2 text 2 and sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 3 text 3 book sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 4 text 4 dice sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 5 text 5 game sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 6 text 6 ghosts sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 7 text 7 goblins sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 8 text 8 i sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 9 text 9 illustrated sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 10 text 10 me sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 11 text 11 monsters sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 12 text 12 myself sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 13 text 13 of sequence_onehot_9p9uj

#> 14 text 14 spooky sequence_onehot_9p9ujIf we take a look at the resulting matrix, we have one row per observation. The first row starts with some padded zeroes but then contains 1, 4, and 5, which we can use together with the vocabulary to construct the original sentence.

prep(small_spec) %>%

bake(new_data = NULL, composition = "matrix")#> _text_1 _text_2 _text_3 _text_4 _text_5 _text_6

#> [1,] 0 0 0 1 4 5

#> [2,] 0 0 0 14 4 5

#> [3,] 0 0 9 3 13 11

#> [4,] 6 7 10 12 2 8

When we bake() a prepped recipe, we apply the preprocessing to a data set. We can get out the training set that we started with by specifying new_data = NULL or apply it to another set via new_data = my_other_data_set. The output of bake() is a data set like a tibble or a matrix, depending on the composition argument.

But wait, the 4th line should have started with an 11 since the sentence starts with “monsters!” The entry in _text_1 is 6 instead. This is happening because the sentence is too long to fit inside the specified sequence length. We must answer three questions before using step_sequence_onehot():

- How long should the output sequence be?

- What happens to sequences that are too long?

- What happens to sequences that are too short?

Choosing the right sequence length is a balancing act. You want the length to be long enough such that you don’t truncate too much of your text data, but still short enough to keep the size of the data manageable and to avoid excessive padding. Truncating, having large training data, and excessive padding all lead to worse model performance. This parameter is controlled by the sequence_length argument in step_sequence_onehot().

If the sequence is too long, then it must be truncated. This can be done by removing values from the beginning ("pre") or the end ("post") of the sequence. This choice is mostly influenced by the data, and you need to evaluate where most of the useful information of the text is located. News articles typically start with the main points and then go into detail. If your goal is to detect the broad category, then you may want to keep the beginning of the texts, whereas if you are working with speeches or conversational text, then you might find that the last thing to be said carries more information.

Lastly, we need to decide how to pad a document that is too short. Pre-padding tends to be more popular, especially when working with RNN and LSTM models (Chapter 9) since having post-padding could result in the hidden states getting flushed out by the zeroes before getting to the text itself (Section 9.5).

The defaults for step_sequence_onehot() are sequence_length = 100, padding = "pre", and truncating = "pre". If we change the truncation to happen at the end with:

recipe(~ text, data = small_data) %>%

step_tokenize(text) %>%

step_sequence_onehot(text, sequence_length = 6, prefix = "",

padding = "pre", truncating = "post") %>%

prep() %>%

bake(new_data = NULL, composition = "matrix")#> _text_1 _text_2 _text_3 _text_4 _text_5 _text_6

#> [1,] 0 0 0 1 4 5

#> [2,] 0 0 0 14 4 5

#> [3,] 0 0 9 3 13 11

#> [4,] 11 6 7 10 12 2then we see the 11 at the beginning of the last row representing the “monsters.” The starting points are not aligned since we are still padding on the left side. We can left-align all the sequences by setting padding = "post".

recipe(~ text, data = small_data) %>%

step_tokenize(text) %>%

step_sequence_onehot(text, sequence_length = 6, prefix = "",

padding = "post", truncating = "post") %>%

prep() %>%

bake(new_data = NULL, composition = "matrix")#> _text_1 _text_2 _text_3 _text_4 _text_5 _text_6

#> [1,] 1 4 5 0 0 0

#> [2,] 14 4 5 0 0 0

#> [3,] 9 3 13 11 0 0

#> [4,] 11 6 7 10 12 2Now we have all digits representing the first characters neatly aligned in the first column.

Let’s now prepare and apply our feature engineering recipe kick_rec so we can use it in for our deep learning model.

kick_prep <- prep(kick_rec)

kick_train <- bake(kick_prep, new_data = NULL, composition = "matrix")

dim(kick_train)#> [1] 202092 30The matrix kick_train has 202,092 rows, corresponding to the rows of the training data, and 30 columns, corresponding to our chosen sequence length.

8.2.3 Simple flattened dense network

Our first deep learning model embeds these Kickstarter blurbs in sequences of vectors, flattens them, and then trains a dense network layer to predict whether the campaign was successful or not.

library(keras)

dense_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words + 1,

output_dim = 12,

input_length = max_length) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

dense_model#> Model: "sequential"

#> ________________________________________________________________________________

#> Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

#> ================================================================================

#> embedding (Embedding) (None, 30, 12) 240012

#> ________________________________________________________________________________

#> flatten (Flatten) (None, 360) 0

#> ________________________________________________________________________________

#> dense_1 (Dense) (None, 32) 11552

#> ________________________________________________________________________________

#> dense (Dense) (None, 1) 33

#> ================================================================================

#> Total params: 251,597

#> Trainable params: 251,597

#> Non-trainable params: 0

#> ________________________________________________________________________________Let us step through this model specification one layer at a time.

We initiate the Keras model by using

keras_model_sequential()to indicate that we want to compose a linear stack of layers.Our first

layer_embedding()is equipped to handle the preprocessed data we have inkick_train. It will take each observation/row inkick_trainand make dense vectors from our word sequences. This turns each observation into anembedding_dim\(\times\)sequence_lengthmatrix, 12 \(\times\) 30 matrix in our case. In total, we will create anumber_of_observations\(\times\)embedding_dim\(\times\)sequence_lengthdata cube.The next

layer_flatten()layer takes the matrix for each observation and flattens them into one dimension. This will create a30 * 12 = 360long vector for each observation.Lastly, we have 2 densely connected layers. The last layer has a sigmoid activation function to give us an output between 0 and 1, since we want to model a probability for a binary classification problem.

We still have a few things left to add to this model before we can fit it to the data. A Keras model requires an optimizer and a loss function to be able to compile.

When the neural network finishes passing a batch of data through the network, it needs a way to use the difference between the predicted values and true values to update the network’s weights. The algorithm that determines those weights is known as the optimization algorithm. Many optimizers are available within Keras itself11; you can even create custom optimizers if what you need isn’t on the list. We will start by using the Adam optimizer, a good default optimizer for many problems.

An optimizer can either be set with the name of the optimizer as a character or by supplying the function optimizer_foo() where foo is the name of the optimizer. If you use the function then you can specify parameters for the optimizer.

During training of a neural network, there must be some quantity that we want to have minimized; this is called the loss function. Again, many loss functions are available within Keras12. These loss functions typically have two arguments, the true value and the predicted value, and return a measure of how close they are. Since we are working on a binary classification task and the final layer of the network returns a probability, binary cross-entropy is an appropriate loss function. Binary cross-entropy does well at dealing with probabilities because it measures the “distance” between probability distributions. In our case, this would be the ground-truth distribution and the predictions.

We can also add any number of metrics13 to be calculated and reported during training. These metrics will not affect the training loop, which is controlled by the optimizer and loss function. The metrics’ only job is to report back a single number that will inform you how well the model is performing. We will select accuracy as a reported metric for now.

Let’s set these three options (optimizer, loss, and metrics) using the compile() function:

dense_model %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)

Notice how the compile() function modifies the model in place. This is different from how objects are conventionally handled in R so be vigilant about model definition and modification in your code. This is a conscious decision that was made when creating the keras R package to match the data structures and behavior of the underlying Keras library.

Finally, we can fit this model! We need to supply the data for training as a matrix of predictors x and a numeric vector of labels y.

This is sufficient information to get started training the model, but we are going to specify a few more arguments to get better control of the training loop. First, we set the number of observations to pass through at a time with batch_size, and we set epochs = 20 to tell the model to pass all the training data through the training loop 20 times. Lastly, we set validation_split = 0.25 to specify an internal validation split; this will keep 25% of the data for validation.

dense_history <- dense_model %>%

fit(

x = kick_train,

y = kickstarter_train$state,

batch_size = 512,

epochs = 20,

validation_split = 0.25,

verbose = FALSE

)We can visualize the results of the training loop by plotting the dense_history in Figure 8.5.

plot(dense_history)FIGURE 8.5: Training and validation metrics for dense network

We have dealt with accuracy in other chapters; remember that a higher value (a value near one) is better. Loss is new in these deep learning chapters, and a lower value is better.

The loss and accuracy both improve with more training epochs on the training data; this dense network more and more closely learns the characteristics of the training data as its trains longer. The same is not true of the validation data, the held-out 25% specified by validation_split = 0.25. The performance is worse on the validation data than the testing data, and degrades somewhat as training continues. If we wanted to use this model, we would want to only train it about 7 or 8 epochs.

8.2.4 Evaluation

For our first deep learning model, we used the Keras defaults for creating a validation split and tracking metrics, but we can use tidymodels functions to be more specific about these model characteristics. Instead of using the validation_split argument to fit(), we can create our own validation set using tidymodels and use validation_data argument for fit(). We create our validation split from the training set.

set.seed(234)

kick_val <- validation_split(kickstarter_train, strata = state)

kick_val#> # Validation Set Split (0.75/0.25) using stratification

#> # A tibble: 1 × 2

#> splits id

#> <list> <chr>

#> 1 <split [151568/50524]> validationThe split object contains the information necessary to extract the data we will use for training/analysis and the data we will use for validation/assessment. We can extract these data sets in their raw, unprocessed form from the split using the helper functions analysis() and assessment(). Then, we can apply our prepped preprocessing recipe kick_prep to both to transform this data to the appropriate format for our neural network architecture.

kick_analysis <- bake(kick_prep, new_data = analysis(kick_val$splits[[1]]),

composition = "matrix")

dim(kick_analysis)#> [1] 151568 30kick_assess <- bake(kick_prep, new_data = assessment(kick_val$splits[[1]]),

composition = "matrix")

dim(kick_assess)#> [1] 50524 30These are each matrices now appropriate for a deep learning model like the one we trained in the previous section. We will also need the outcome variables for both sets.

state_analysis <- analysis(kick_val$splits[[1]]) %>% pull(state)

state_assess <- assessment(kick_val$splits[[1]]) %>% pull(state)Let’s set up our same dense neural network architecture.

dense_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words + 1,

output_dim = 12,

input_length = max_length) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

dense_model %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)Now we can fit this model to kick_analysis and validate on kick_assess. Let’s only fit for 10 epochs this time.

val_history <- dense_model %>%

fit(

x = kick_analysis,

y = state_analysis,

batch_size = 512,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = list(kick_assess, state_assess),

verbose = FALSE

)

val_history#>

#> Final epoch (plot to see history):

#> loss: 0.03612

#> accuracy: 0.9917

#> val_loss: 1.056

#> val_accuracy: 0.8072Figure 8.6 still shows significant overfitting at 10 epochs.

plot(val_history)FIGURE 8.6: Training and validation metrics for dense network with validation set

Using our own validation set also allows us to flexibly measure performance using tidymodels functions from the yardstick package. We do need to set up a few transformations between Keras and tidymodels to make this work.

The following function keras_predict() creates a little bridge between the two frameworks, combining a Keras model with baked (i.e., preprocessed) data and returning the predictions in a tibble format.

library(dplyr)

keras_predict <- function(model, baked_data, response) {

predictions <- predict(model, baked_data)[, 1]

tibble(

.pred_1 = predictions,

.pred_class = if_else(.pred_1 < 0.5, 0, 1),

state = response

) %>%

mutate(across(c(state, .pred_class), ## create factors

~ factor(.x, levels = c(1, 0)))) ## with matching levels

}This function only works with binary classification models that take a preprocessed matrix as input and return a single probability for each observation. It returns both the predicted probability as well as the predicted class, using a 50% probability threshold.

This function creates prediction results that seamlessly connect with tidymodels and yardstick functions.

val_res <- keras_predict(dense_model, kick_assess, state_assess)

val_res#> # A tibble: 50,524 × 3

#> .pred_1 .pred_class state

#> <dbl> <fct> <fct>

#> 1 0.0225 0 0

#> 2 0.00753 0 0

#> 3 0.0000775 0 0

#> 4 0.0000660 0 0

#> 5 1.00 1 1

#> 6 0.996 1 1

#> 7 0.0000000455 0 0

#> 8 0.00155 0 0

#> 9 0.979 1 1

#> 10 1.00 1 1

#> # … with 50,514 more rowsWe can calculate the standard metrics with metrics().

metrics(val_res, state, .pred_class)#> # A tibble: 2 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy binary 0.807

#> 2 kap binary 0.613This matches what we saw when we looked at the output of val_history.

Since we have access to tidymodels’ full capacity for model evaluation, we can also compute confusion matrices and ROC curves. The heatmap in Figure 8.7 shows that there isn’t any dramatic bias in how the model performs for the two classes, success and failure for the crowdfunding campaigns. The model certainly isn’t perfect; its accuracy is a little over 80%, but at least it is more or less evenly good at predicting both classes.

val_res %>%

conf_mat(state, .pred_class) %>%

autoplot(type = "heatmap")FIGURE 8.7: Confusion matrix for first DNN model predictions of Kickstarter campaign success

The ROC curve in Figure 8.8 shows how the model performs at different thresholds.

val_res %>%

roc_curve(truth = state, .pred_1) %>%

autoplot() +

labs(

title = "Receiver operator curve for Kickstarter blurbs"

)FIGURE 8.8: ROC curve for first DNN model predictions of Kickstarter campaign success

8.3 Using bag-of-words features

Before we move on with neural networks and this new way to represent the text sequences, let’s explore what happens if we use the same preprocessing as in Chapters 6 and 7. We will employ a bag-of-words preprocessing and input word counts only to the neural network. This model will not use any location-based information about the tokens, just the counts.

For this, we need to create a new recipe to transform the data into counts.

The objects in this chapter are named using bow to indicate that they are using bag of word data.

kick_bow_rec <- recipe(~ blurb, data = kickstarter_train) %>%

step_tokenize(blurb) %>%

step_stopwords(blurb) %>%

step_tokenfilter(blurb, max_tokens = 1e3) %>%

step_tf(blurb)We will prep() and bake() this recipe to get out our processed data. The result will be quite sparse, since the blurbs are short, and we are counting only the most frequent 1000 tokens after removing the Snowball stop word list.

kick_bow_prep <- prep(kick_bow_rec)

kick_bow_analysis <- bake(kick_bow_prep,

new_data = analysis(kick_val$splits[[1]]),

composition = "matrix")

kick_bow_assess <- bake(kick_bow_prep,

new_data = assessment(kick_val$splits[[1]]),

composition = "matrix")Now that we have the analysis and assessment data sets calculated, we can define the neural network architecture. We won’t be using an embedding layer this time; we will input the word count data directly into the first dense layer. This dense layer is followed by another hidden layer and then a final layer with a sigmoid activation to leave us with a value between 0 and 1 that we treat as the probability.

bow_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense(units = 64, activation = "relu", input_shape = c(1e3)) %>%

layer_dense(units = 64, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

bow_model %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)In many ways, this model architecture is not that different from the model we used in Section 8.2. The main difference here is the preprocessing; the shape and information of the data from kick_bow_prep are different from what we saw before since the matrix elements represent counts (something that Keras can handle directly) and not indicators for words in the vocabulary. Keras handles the indicators with layer_embedding(), by mapping them through an embedding layer.

The fitting procedure remains unchanged.

bow_history <- bow_model %>%

fit(

x = kick_bow_analysis,

y = state_analysis,

batch_size = 512,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = list(kick_bow_assess, state_assess),

verbose = FALSE

)

bow_history#>

#> Final epoch (plot to see history):

#> loss: 0.3288

#> accuracy: 0.8574

#> val_loss: 0.6662

#> val_accuracy: 0.724We use keras_predict() again to get predictions, and calculate the standard metrics with metrics().

bow_res <- keras_predict(bow_model, kick_bow_assess, state_assess)

metrics(bow_res, state, .pred_class)#> # A tibble: 2 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy binary 0.724

#> 2 kap binary 0.446This model does not perform as well as the model we used in Section 8.2. This suggests that a model incorporating more than word counts alone is useful here. This model did outperform a baseline linear model (shown in Appendix C), which achieved an accuracy of 0.686; that linear baseline is a regularized linear model trained on the same data set, using tf-idf weights and 5000 tokens.

This simpler model does not outperform our initial model in this chapter, but it is typically worthwhile to investigate if a simpler model can rival or beat a model we are working with.

8.4 Using pre-trained word embeddings

The models in Section 8.2 included an embedding layer to make dense vectors from our word sequences that the model learned, along with the rest of the model as a whole. This is not the only way to handle this task. In Chapter 5, we examined how word embeddings are created and how they are used. Instead of having the embedding layer start randomly and be trained alongside the other parameters, let’s try to provide the embeddings.

This section serves to show how to use pre-trained word embeddings, but in most realistic situations, your data and pre-trained embeddings may not match well. The main takeaways from this section should be that this approach is possible and how you can get started with it. Keep in mind that it may not be appropriate for your data and problem.

We start by obtaining pre-trained embeddings. The GloVe embeddings that we used in Section 5.4 are a good place to start. Setting dimensions = 50 and only selecting the first 12 dimensions will make it easier for us to compare to our previous models directly.

library(textdata)

glove6b <- embedding_glove6b(dimensions = 50) %>% select(1:13)

glove6b#> # A tibble: 400,000 × 13

#> token d1 d2 d3 d4 d5 d6 d7 d8 d9

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 "the" 0.418 0.250 -0.412 0.122 0.345 -0.0445 -0.497 -0.179 -0.000660

#> 2 "," 0.0134 0.237 -0.169 0.410 0.638 0.477 -0.429 -0.556 -0.364

#> 3 "." 0.152 0.302 -0.168 0.177 0.317 0.340 -0.435 -0.311 -0.450

#> 4 "of" 0.709 0.571 -0.472 0.180 0.544 0.726 0.182 -0.524 0.104

#> 5 "to" 0.680 -0.0393 0.302 -0.178 0.430 0.0322 -0.414 0.132 -0.298

#> 6 "and" 0.268 0.143 -0.279 0.0163 0.114 0.699 -0.513 -0.474 -0.331

#> 7 "in" 0.330 0.250 -0.609 0.109 0.0364 0.151 -0.551 -0.0742 -0.0923

#> 8 "a" 0.217 0.465 -0.468 0.101 1.01 0.748 -0.531 -0.263 0.168

#> 9 "\"" 0.258 0.456 -0.770 -0.377 0.593 -0.0635 0.205 -0.574 -0.290

#> 10 "'s" 0.237 0.405 -0.205 0.588 0.655 0.329 -0.820 -0.232 0.274

#> # … with 399,990 more rows, and 3 more variables: d10 <dbl>, d11 <dbl>,

#> # d12 <dbl>The embedding_glove6b() function returns a tibble; this isn’t the right format for Keras. Also, notice how many rows are present in this embedding, far more than what the trained recipe is expecting. The vocabulary can be extracted from the trained recipe using tidy(). Let’s apply tidy() to kick_prep to get the list of steps that the recipe contains.

tidy(kick_prep)#> # A tibble: 3 × 6

#> number operation type trained skip id

#> <int> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <lgl> <chr>

#> 1 1 step tokenize TRUE FALSE tokenize_nHrhX

#> 2 2 step tokenfilter TRUE FALSE tokenfilter_2TrDo

#> 3 3 step sequence_onehot TRUE FALSE sequence_onehot_H16cBWe see that the third step is the sequence_onehot step, so by setting number = 3 we can extract the embedding vocabulary.

tidy(kick_prep, number = 3)#> # A tibble: 20,000 × 4

#> terms vocabulary token id

#> <chr> <int> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 blurb 1 0 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 2 blurb 2 00 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 3 blurb 3 000 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 4 blurb 4 00pm sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 5 blurb 5 01 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 6 blurb 6 02 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 7 blurb 7 03 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 8 blurb 8 05 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 9 blurb 9 07 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> 10 blurb 10 09 sequence_onehot_H16cB

#> # … with 19,990 more rowsWe can then use left_join() to combine these tokens to the glove6b embedding tibble and only keep the tokens of interest. We replace any tokens from the vocabulary not found in glove6b with 0 using mutate_all() and replace_na(). We can transform the results into a matrix, and add a row of zeroes at the top of the matrix to account for the out-of-vocabulary words.

glove6b_matrix <- tidy(kick_prep, 3) %>%

select(token) %>%

left_join(glove6b, by = "token",) %>%

mutate(across(!token, replace_na, 0)) %>%

select(-token) %>%

as.matrix() %>%

rbind(0, .)We’ll keep the model architecture itself as unchanged as possible. The output_dim argument is set equal to ncol(glove6b_matrix) to make sure that all the dimensions line up correctly, but everything else stays the same.

dense_model_pte <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words + 1,

output_dim = ncol(glove6b_matrix),

input_length = max_length) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")Now we use get_layer() to access the first layer (which is the embedding layer), set the weights with set_weights(), and then freeze the weights with freeze_weights().

Freezing the weights stops them from being updated during the training loop.

dense_model_pte %>%

get_layer(index = 1) %>%

set_weights(list(glove6b_matrix)) %>%

freeze_weights()Now we compile and fit the model just like the last one we looked at.

dense_model_pte %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)

dense_pte_history <- dense_model_pte %>%

fit(

x = kick_analysis,

y = state_analysis,

batch_size = 512,

epochs = 20,

validation_data = list(kick_assess, state_assess),

verbose = FALSE

)

dense_pte_history#>

#> Final epoch (plot to see history):

#> loss: 0.5954

#> accuracy: 0.68

#> val_loss: 0.6702

#> val_accuracy: 0.613This model is not performing well at all! We can confirm by computing metrics on our validation set.

pte_res <- keras_predict(dense_model_pte, kick_assess, state_assess)

metrics(pte_res, state, .pred_class)#> # A tibble: 2 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy binary 0.613

#> 2 kap binary 0.222Why did this happen? Part of the training loop for a model like this one typically adjusts the weights in the network. When we froze the weights in this network, we froze them at values that did not perform very well. These pre-trained GloVe embeddings (Pennington, Socher, and Manning 2014) are trained on a Wikipedia dump and Gigaword 5, a comprehensive archive of newswire text. The text contained on Wikipedia and in news articles both follow certain styles and semantics. Both will tend to be written formally and in the past tense, with longer and complete sentences. There are many more distinct features of both Wikipedia text and news articles, but the relevant aspect here is how similar they are to the data we are trying to model. These Kickstarter blurbs are very short, lack punctuation, stop words, narrative, and tense. Many of the blurbs simply try to pack as many buzz words as possible into the allowed character count while keeping the sentence readable. Perhaps it should not surprise us that these word embeddings don’t perform well in this model, since the text used to train the embeddings is so different from the text is it being applied to (Section 5.4).

Although this approach didn’t work well with our data set, that doesn’t mean that using pre-trained word embeddings is always a bad idea.

The key point is how well the embeddings match the data you are modeling. Also, there is another way we can use these particular embeddings in our network architecture; we can load them in as a starting point as before but not freeze the weights. This allows the model to adjust the weights to better fit the data. The intention here is that we as the modeling practitioners think these pre-trained embeddings offer a better starting point than the randomly generated embedding we get if we don’t set the weights at all.

We specify a new model to get started on this approach.

dense_model_pte2 <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words + 1,

output_dim = ncol(glove6b_matrix),

input_length = max_length) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")Now, we set the weights with set_weights(), but we don’t freeze them.

dense_model_pte2 %>%

get_layer(index = 1) %>%

set_weights(list(glove6b_matrix))We compile and fit the model as before.

dense_model_pte2 %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)

dense_pte2_history <- dense_model_pte2 %>% fit(

x = kick_analysis,

y = state_analysis,

batch_size = 512,

epochs = 20,

validation_data = list(kick_assess, state_assess),

verbose = FALSE

)How did this version of using pre-trained embeddings do?

pte2_res <- keras_predict(dense_model_pte2, kick_assess, state_assess)

metrics(pte2_res, state, .pred_class)#> # A tibble: 2 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy binary 0.766

#> 2 kap binary 0.532This performs quite a bit better than when we froze the weights, although not as well as when we did not use pre-trained embeddings at all.

8.5 Cross-validation for deep learning models

The Kickstarter data set we are using is big enough that we have adequate data to use a single training set, validation set, and testing set that all contain enough observations in them to give reliable performance metrics. In some situations, you may not have that much data or you may want to compute more precise performance metrics. In those cases, it is time to turn to resampling. For example, we can create cross-validation folds.

set.seed(345)

kick_folds <- vfold_cv(kickstarter_train, v = 5)

kick_folds#> # 5-fold cross-validation

#> # A tibble: 5 × 2

#> splits id

#> <list> <chr>

#> 1 <split [161673/40419]> Fold1

#> 2 <split [161673/40419]> Fold2

#> 3 <split [161674/40418]> Fold3

#> 4 <split [161674/40418]> Fold4

#> 5 <split [161674/40418]> Fold5Each of these folds has an analysis/training set and an assessment/validation set. Instead of training our model one time and getting one measure of performance, we can train our model v times and get v measures, for more reliability.

In our previous chapters, we used models with full tidymodels support and functions like add_recipe() and workflow(). Deep learning models are more modular and unique, so we will need to create our own function to handle preprocessing, fitting, and evaluation.

fit_split <- function(split, prepped_rec) {

## preprocessing

x_train <- bake(prepped_rec, new_data = analysis(split),

composition = "matrix")

x_val <- bake(prepped_rec, new_data = assessment(split),

composition = "matrix")

## create model

y_train <- analysis(split) %>% pull(state)

y_val <- assessment(split) %>% pull(state)

mod <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words + 1,

output_dim = 12,

input_length = max_length) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid") %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)

## fit model

mod %>%

fit(

x_train,

y_train,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val),

batch_size = 512,

verbose = FALSE

)

## evaluate model

keras_predict(mod, x_val, y_val) %>%

metrics(state, .pred_class, .pred_1)

}We can map() this function across all our cross-validation folds. This takes longer than our previous models to train, since we are training for 10 epochs each on 5 folds.

cv_fitted <- kick_folds %>%

mutate(validation = map(splits, fit_split, kick_prep))

cv_fitted#> # 5-fold cross-validation

#> # A tibble: 5 × 3

#> splits id validation

#> <list> <chr> <list>

#> 1 <split [161673/40419]> Fold1 <tibble [4 × 3]>

#> 2 <split [161673/40419]> Fold2 <tibble [4 × 3]>

#> 3 <split [161674/40418]> Fold3 <tibble [4 × 3]>

#> 4 <split [161674/40418]> Fold4 <tibble [4 × 3]>

#> 5 <split [161674/40418]> Fold5 <tibble [4 × 3]>Now we can use unnest() to find the metrics we computed.

cv_fitted %>%

unnest(validation)#> # A tibble: 20 × 5

#> splits id .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <list> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 <split [161673/40419]> Fold1 accuracy binary 0.818

#> 2 <split [161673/40419]> Fold1 kap binary 0.636

#> 3 <split [161673/40419]> Fold1 mn_log_loss binary 1.07

#> 4 <split [161673/40419]> Fold1 roc_auc binary 0.856

#> 5 <split [161673/40419]> Fold2 accuracy binary 0.819

#> 6 <split [161673/40419]> Fold2 kap binary 0.638

#> 7 <split [161673/40419]> Fold2 mn_log_loss binary 1.02

#> 8 <split [161673/40419]> Fold2 roc_auc binary 0.857

#> 9 <split [161674/40418]> Fold3 accuracy binary 0.820

#> 10 <split [161674/40418]> Fold3 kap binary 0.640

#> 11 <split [161674/40418]> Fold3 mn_log_loss binary 0.983

#> 12 <split [161674/40418]> Fold3 roc_auc binary 0.858

#> 13 <split [161674/40418]> Fold4 accuracy binary 0.818

#> 14 <split [161674/40418]> Fold4 kap binary 0.634

#> 15 <split [161674/40418]> Fold4 mn_log_loss binary 1.03

#> 16 <split [161674/40418]> Fold4 roc_auc binary 0.855

#> 17 <split [161674/40418]> Fold5 accuracy binary 0.820

#> 18 <split [161674/40418]> Fold5 kap binary 0.639

#> 19 <split [161674/40418]> Fold5 mn_log_loss binary 1.00

#> 20 <split [161674/40418]> Fold5 roc_auc binary 0.862We can summarize the unnested results to match what we normally would get from collect_metrics()

cv_fitted %>%

unnest(validation) %>%

group_by(.metric) %>%

summarize(

mean = mean(.estimate),

n = n(),

std_err = sd(.estimate) / sqrt(n)

)#> # A tibble: 4 × 4

#> .metric mean n std_err

#> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy 0.819 5 0.000523

#> 2 kap 0.637 5 0.00106

#> 3 mn_log_loss 1.02 5 0.0153

#> 4 roc_auc 0.858 5 0.00110This data set is large enough that we probably wouldn’t need to take this approach, and the fold-to-fold metrics have little variance. However, resampling can, at times, be an important piece of the modeling toolkit even for deep learning models.

Training deep learning models typically takes more time than other kinds of machine learning, so resampling may be an unfeasible choice. There is special hardware available that speeds up deep learning because it is particularly well-suited to fitting such models. GPUs (graphics processing units) are used for displaying graphics (as indicated in their name) and gaming, but also for deep learning because of their highly parallel computational ability. GPUs can make solving deep learning problems faster, or even tractable to start with. Be aware, though, that you might not need a GPU for even real-world deep learning modeling. All the models in this book were trained on a CPU only.

8.6 Compare and evaluate DNN models

Let’s return to the results we evaluated on a single validation set. We can combine all the predictions on these last three models to more easily compare the results between them.

all_dense_model_res <- bind_rows(

val_res %>% mutate(model = "dense"),

pte_res %>% mutate(model = "pte (locked weights)"),

pte2_res %>% mutate(model = "pte (not locked weights)")

)Now that the results are combined in all_dense_model_res, we can calculate group-wise evaluation statistics by grouping by the model variable.

all_dense_model_res %>%

group_by(model) %>%

metrics(state, .pred_class)#> # A tibble: 6 × 4

#> model .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 dense accuracy binary 0.807

#> 2 pte (locked weights) accuracy binary 0.614

#> 3 pte (not locked weights) accuracy binary 0.764

#> 4 dense kap binary 0.613

#> 5 pte (locked weights) kap binary 0.225

#> 6 pte (not locked weights) kap binary 0.528We can also do this for ROC curves. Figure 8.9 shows the three different ROC curves together in one chart. As we know, the model using pre-trained word embeddings with locked weights didn’t perform very well at all and its ROC curve is the lowest of the three. The other two models perform more similarly but the model using an embedding learned from scratch ends up being the best.

all_dense_model_res %>%

group_by(model) %>%

roc_curve(truth = state, .pred_1) %>%

autoplot() +

labs(

title = "Receiver operator curve for Kickstarter blurbs"

)FIGURE 8.9: ROC curve for all DNN models’ predictions of Kickstarter campaign success

transformers models available from Hugging Face. Check out this blog post for a tutorial on how to use Hugging Face transfomers in R with Keras. Large language models like these are subject to many of the same concerns as embeddings discussed in Section 5.5.

We compared these three model options using the validation set we created. Let’s return to the testing set now that we know which model we expect to perform best and obtain a final estimate for how we expect it to perform on new data. For this final evaluation, we will:

preprocess the test data using the feature engineering recipe

kick_prepso it is in the correct format for our deep learning model,find the predictions for the processed testing data, and

compute metrics for these results.

kick_test <- bake(kick_prep, new_data = kickstarter_test,

composition = "matrix")

final_res <- keras_predict(dense_model, kick_test, kickstarter_test$state)

final_res %>% metrics(state, .pred_class, .pred_1)#> # A tibble: 4 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy binary 0.807

#> 2 kap binary 0.612

#> 3 mn_log_loss binary 1.06

#> 4 roc_auc binary 0.848The metrics we see here are about the same as what we achieved in Section 8.2.4 on the validation data, so we can be confident that we have not overfit during our training or model choosing process.

Just like we did toward the end of both Sections 6.9.4 and 7.11.3, we can look at some examples of test set observations that our model did a bad job at predicting. Let’s bind together the predictions on the test set with the original kickstarter_test data. Then let’s look at blurbs that were successful but that our final model thought had a low probability of being successful.

kickstarter_bind <- final_res %>%

bind_cols(kickstarter_test %>% select(-state))

kickstarter_bind %>%

filter(state == 1, .pred_1 < 0.2) %>%

select(blurb) %>%

slice_sample(n = 10)#> # A tibble: 10 × 1

#> blurb

#> <chr>

#> 1 "A struggling writer has a chance encounter with a mysterious man whose life…

#> 2 "Help support Ryan to start his project on healing foods with his trip to Du…

#> 3 "A box set of media celebrating EarthBound and the fans who have kept it ali…

#> 4 "We want to take our music to the next level by recording our two latest sin…

#> 5 "So far I've only written five reasons, so I'm going to write seven more. Al…

#> 6 "The prequel episode for Season 2 bridges the events of Season 1. More effec…

#> 7 "Emmanuel Odhiambo aka huthead is a musician from Kenya, discovered by Peace…

#> 8 "The stories behind the remaking of New York's most populous borough."

#> 9 "More than just an awesome t-shirt: A revolutionary way to support victims o…

#> 10 "Bring Plasma Frequency magazine back after they faced devastating bank frau…What about misclassifications in the other direction, observations in the test set that were not successful but that our final model gave a high probability of being successful?

kickstarter_bind %>%

filter(state == 0, .pred_1 > 0.8) %>%

select(blurb) %>%

slice_sample(n = 10)#> # A tibble: 10 × 1

#> blurb

#> <chr>

#> 1 "Please help me record my first solo album!! It will blow your mind! Check …

#> 2 "We are designing and building a new adaptive housing model for aging Americ…

#> 3 "Big in Britain--a funny,modern,sexy love-story."

#> 4 "Hope's Wish is the story of Hope Stout who raised over $1MM to grant the wi…

#> 5 "The third game in the classic The 7th Guest series from Trilobyte Games."

#> 6 "Do, It. Do it now. MASTER MIND ALLIANCE PUBLISHING, 2013. DO IT FOO. :))))…

#> 7 "Carl The Comet is an educational kids picture book yet also entertainment, …

#> 8 "Help rehabilitation counselors, John and Jessica Freeborn, develop and publ…

#> 9 "As the title says, this is a project to destroy iphones in different ways, …

#> 10 "S.S.U.C drops their second single \"She Bad\" April 2013. Help us showcase…Notice that although some steps for model fitting are different now that we are using deep learning, model evaluation is much the same as it was in Chapters 6 and 7.

8.7 Limitations of deep learning

Deep learning models achieve excellent performance on many tasks; the flexibility and potential complexity of their architecture is part of the reason why. One of the main downsides of deep learning models is that the interpretability of the models themselves is poor.

Notice that we have not talked about which words are more associated with success or failure for the Kickstarter campaigns in this whole chapter!

This means that practitioners who work in fields where interpretability is vital, such as some parts of health care, shy away from deep learning models since they are hard to understand and interpret.

Another limitation of deep learning models is that they do not facilitate a comprehensive theoretical understanding or learning of their inner organization (Shwartz-Ziv and Tishby 2017). These two points together lead to deep learning models often being called “black box” models (Shrikumar, Greenside, and Kundaje 2017), models where is it hard to peek into the inner workings to understand what they are doing. Not being able to reason about the inner workings of a model means that we will have a hard time explaining why a model is working well. It also means it will be hard to remedy a biased model that performs well in some settings but badly in other settings. This is a problem since it can hide biases from the training set that may lead to unfair, wrong, or even illegal decisions based on protected classes (Guidotti et al. 2018).

Practitioners have built approaches to understand local feature importance for deep learning models, which we demonstrate in Section 10.5, but these are limited tools compared to the interpretability of other kinds of models. Lastly, deep learning models tend to require more training data than traditional statistical machine learning methods. This means that it can be hard to train a deep learning model if you have a very small data set (Lampinen and McClelland 2018).

8.8 Summary

You can use deep learning to build classification models to predict labels or categorical variables from a data set, including data sets that include text. Dense neural networks are the most straightforward network architecture that can be used to fit classification models for text features and are a good bridge for understanding the more complex model architectures that are used more often in practice for text modeling. These models have many parameters compared to the models we trained in earlier chapters, and require different preprocessing than those models. We can tokenize and create features for modeling that capture the order of the tokens in the original text. Doing this can allow a model to learn from patterns in sequences and order, something not possible in the models we saw in Chapters 6 and 7. We gave up some of the fine control over feature engineering, such as hand-crafting features using domain knowledge, in the hope that the network could learn important features on its own. However, feature engineering is not completely out of our hands as practitioners, since we still make decisions about tokenization and normalization before the tokens are passed into the network.

8.8.1 In this chapter, you learned:

that you can tokenize and preprocess text to retain the order of the tokens

how to build and train a dense neural network with Keras

that you can evaluate deep learning models with the same approaches used for other types of models

how to train word embeddings alongside your model

how to use pre-trained word embeddings in a neural network

about resampling strategies for deep learning models

about the low interpretability of deep learning models

References

The

termscolumn refers to the column we have appliedstep_sequence_onehot()to andidis its unique identifier. Note that textrecipes allowsstep_sequence_onehot()to be applied to multiple text variables independently, and they will have their own vocabularies.↩︎